Mean Mail

I will call her Mary.

Of course, even all these months later, I do remember her real name. I remember it as clearly as I do the words she used to describe me: “sham,” “self-absorbed,” “selfish,” and “failure.” I remember reading those words with my heart pounding, my hands shaking, my mouth going dry.

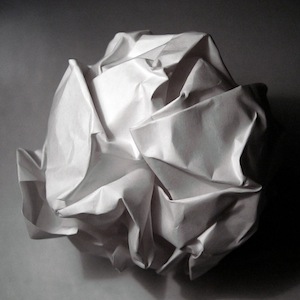

I remember how deeply they cut, how defenseless and ashamed they made me feel, how brutally close to the mark they came. I remember that, alone in my kitchen on a bright winter’s day, I read a letter from a total stranger and crumpled into a ball on the sofa, as if shielding myself from another blow.

I remember that, alone in my kitchen on a bright winter’s day, I read a letter from a total stranger and crumpled into a ball on the sofa, as if shielding myself from another blow.

And yet, the first thing I do when I turn on my computer this morning is retrieve Mary’s long-ago e-mail from my inbox. If my task here is to write about mean mail from readers, I must begin by putting Exhibit A out on the table.

I take a deep breath. And then I read it again, this silent, perfectly aimed strike from a woman who read the first chapters of my most recent book and felt compelled to pause and let me know that although she considers me a “wonderful writer,” who “gets to the heart and soul of a woman’s thinking,” I am a failure as a mother, as a person, as a role model.

If memoir is a slice of curated reality in which not everything that happens shows up on the page, but in which everything that does appear there must be faithfully rendered, then failure probably has to be part of the deal.

We go to self-help books in search of answers. We turn to memoir, I suspect, to engage in a conversation about the questions themselves. Perhaps what we want most of all is both to find ourselves and lose ourselves in the pages of another’s story. We read memoir not to fix our lives, but to see how this person or that one manages to heal their own broken places. We long to know how others play the hand they got dealt, how the path twists and turns beneath another’s feet, whether someone else has survived the wrong turn, the crack up, the heartbreak. We may arrive at memoir’s door hoping for inspiration, but we enter into its rooms to be reminded of the painful truth we already know: life is both beautiful and hard, things rarely go as planned, and no one comes through unscathed.

Which does not make confessing my own shortcomings any easier. The temptation, when I sit down to write, is always there: to offer up a smarter, tidier, more impressive version of myself. How much easier it would be to show up on the page with some answers, some hard-won wisdom, a handful of fool-proof tips about life and parenting and growing older—good, solid advice gleaned from deep reflection and personal experience, neatly packaged and ready for public consumption. How great it would be, I think to myself, to have things all figured out and to write about that.

Instead, my own writing process goes something like this: I procrastinate for a few hours. I get the dishes done, make sure every last crumb is swept from the counter, from the floor. I water the houseplants, throw in a load of laundry, pay a few bills. And then, when I can put it off no longer, I sit down on a stool at the kitchen table. I force myself to stay. I swear off checking e-mail or reviewing the weather forecast online. I watch the shadows lengthen on the wall, feel the hours tick slowly by on the clock.

Eventually, if I am patient and wait long enough, I drop down into the inchoate, confusing place that gives rise to all my own unanswered questions, the messy, troubling stuff that remains unresolved in my heart and that gnaws at my soul in the dark of night.

Slowly, slowly, something inside me begins to open, to settle in, to accept that this feeling of discomfort is indeed my starting place. It isn’t a place of certainty, but rather one of hunger and longing and not knowing. And my job, as I continually remind myself, isn’t to come up with answers, but to find words that might convey the disheveled, imperfect truth of who I really am and how I really feel—the confusion and the fleeting clarity, the despair and the hope, the joy and the heartbreak of being a human being who is wrong about things every bit as often as she’s right.

Perhaps it is in our very nature to fear being found out. Don’t we all get up each morning determined to do the best we can at being the person we aspire to become? And don’t we worry, too, that any minute now we’ll be called out, have our failings exposed, our unsuitability for the job revealed? Try as we might to put the best face forward, there is, deep inside, that persistent, unshakeable, uniquely human fear that we aren’t really all we claim to be, that we are and will always be somehow “less than.”

For a writer, for a memoir writer in particular, the stakes can feel even a bit higher than that. Consider: there is the person I feel myself to be inside. There is the (better!) person I aspire to become. There is the highly fallible person my closest friends and family know and love in spite of everything. There is the somewhat more presentable person who chats with the grocery store clerk and shows up at yoga class. And then, in addition to all those “me’s,” there is another, even more public and considerably less together person who appears on the page. A character who comprises, perhaps, bits and pieces of all these beings.

She is me, but she is also my creation, my own vulnerable, narrated self; the “me” who lives between the covers of a book and who bravely carries my story of how I stumbled from there to here out into the world. She is at once me and not me.

Take a swing at her, though, and I am, without a doubt, the one who feels the punch.

“I’m a very private person,” I once said to my neighbor, in an attempt to explain why I spend so many hours at home alone, why I cherish a day when I don’t have anywhere to go or anything to do but putz around my house in a pair of old sweat pants and a ratty fleece and a pair of flip flops.

“A private person?” She laughed, incredulous. “How could you be? You write about yourself!”

She’s right of course. I do. And yet to do that, I first have to construct and inhabit that illusion of privacy. Sitting alone in my kitchen, dropping down into the dark, difficult place from which truth flows, it is easy—and necessary—to pretend that no one will ever read the pages that accumulate beneath my finger tips.

I cannot write well or honestly if I’m also thinking about the future or anticipating the reaction of some unknown reader. No. My challenge as a writer is simply to be acutely present in this moment, to put down upon the page both what I know and what I don’t know, and to have faith that there is value even in the not knowing. To have faith, too, in this paradoxical process by which the personal becomes universal, individual experience becomes shared experience, one life expresses the unwritten truth of many lives, and words conjured in solitude make their way out into the world to forge connections that didn’t exist before.

Last night, over dinner, I told a friend I was going to write a piece about mean mail from readers. “I said I’d do this months ago,” I confessed, “and now I’m wishing I hadn’t.”

I had thought, back when the wound was fresh and writing about it seemed like a sly way to respond to the hurt, that I would quote Mary’s entire letter here, perhaps even drum up a bit of sympathy from my fellow writers, who could respond with their own war stories of assaults from readers.

But as I re-read Mary’s letter this morning, I realize there is no need to share it here, any more than there is reason for me to defend myself against its accusations. The desire to strike back, to make my case, to have the last word, is long gone.

All I can do—all any of us can do—is write what we know right now from where we are today. I can’t claim to have it right, neither the writing nor the living. To tell one’s own story is to step straight into vulnerability, to open oneself to judgment and criticism. But to write a memoir is also to believe that any human presence, imperfect and undefended, is in itself an offering.

In sharing our innermost struggles, our joys, our sorrows, we invite others to consider their own fumbling steps in the dark with more tenderness. In cultivating empathy for ourselves, for our mistakes and shortcomings, we also clear a space for the stories of others who struggle. That seems to me work worth doing. It is the conversation we long to have, the exchange between reader and writer we are all here for, the reason I am willing to dwell for hours in that uncomfortable place waiting for the words to come.

That sharp-edged essay about mean mail I thought I’d write? It seems I don’t really have it in me. Sitting with Mary’s letter today has reminded me what a blessing it is to soften and what a relief it is to forgive. For better and for worse, the words we write form bridges between us, connecting us soul to soul, heart to heart. The communion isn’t always easy—how could it be? Perhaps it’s the connection itself that matters, though, not the approval. And perhaps the best response to a reader like Mary is to understand that she isn’t hurting me because I’m who I am, but because she’s who she is. Which means there’s nothing I need to defend after all.

And so, all these months later, I drag Exhibit A over to the tiny trashcan in the corner of my screen. I click the icon and let it go.

“Thank God there’s only one of her,” I said to my friend last night, after reciting Mary’s list of accusations from memory. But perhaps what I really want to say is, “Thank God there was one of her” —a sad, angry woman who reached out through the ether to remind me that my challenge, both as a writer and as a person, isn’t to make people like me, but to become a little better at loving and accepting myself.

Read The Story Behind “Mean Mail” on our blog.