My Father’s Engagement Ring

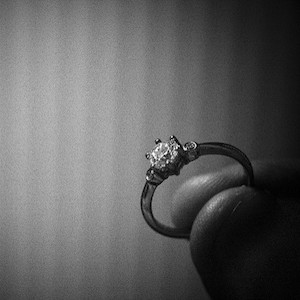

This is a story about love, and in my family love meant money. In 1947, Mr. D. Maizel walked into one of New York City’s Park Avenue jewelers seeking their appraisal of an engagement ring with a diamond flanked by baguettes. That diamond was a crystal doorway opening to radiance, luring light to slide along sharp lines, trapping it to dance in its depths. Held there, too, were flashes of darkness. For some an engagement ring is a beacon cutting through the fog of chores and work, family and friends, life’s daily boredom. For others it’s a symbol of happiness, a promise of life-long love. To Mr. D. Maizel an engagement ring meant money. The appraised price was eight hundred and fifty dollars, which in post-World War II America was a good chunk of change.

As the daughter of the marriage my father’s engagement ring heralded, I inherited that long ago appraisal with its black Courier letters punched by a manual typewriter onto white stationery. I don’t need the appraiser’s note to know this story is true, just as I know the ring’s worth is true, just as I know there never was a Mr. D. Maizel in my family. There was only Miss D. Maizel, my mother, and in 1947 a respectable young woman didn’t have her engagement ring appraised. But a young woman, herself a survivor of the Great Depression (when her father had abandoned her, her mother, her sister and two brothers to near poverty), could leave her office during lunch, go to a Park Avenue jeweler, and claim to be running an errand on behalf of her boss, one Mr. D. Maizel, confident no one would ask for her name. I imagine my mother left the store reassured as to the price my father put on his love, his long-term prospects as a provider, their marriage’s worth.

But marriage is Russian roulette. In those days, decent people didn’t have sex before marriage. They didn’t live together. They didn’t know each other in any way other than infatuation, or at least my parents didn’t. Decent people married to gain their knowledge: a bitter wisdom of incompatibility. My parents were especially naïve. Before marrying, my mother had lived with her mother and sister, just as my father had lived with his mother. My mother was thirty-one when she wed. My father was thirty-eight.

And so my parents’ marriage had more than one bullet loaded in love’s gun. Then came two miscarriages. A daughter born in a botched delivery that nearly killed my mother. And then my birth, surprisingly simple. A few years later my father was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, then and now an incurable neurological disease that triggers tremors and stiffens muscles as if they were stone. At some point my mother wearied of my father’s engagement ring.

I was old enough by then to see my mother hoarded love like pennies. One time she took all her money out of one bank, drove across town, and deposited it in another bank that offered one-half of one-percent more in interest. She bought toys second-hand; she would have battles with me in the women’s section of department stores to purchase an 8-pack of ugly panties decorated with wide-eyed bees that cost fifty-cents less than a different set I wanted. Our family’s living room had expensive brocade couches we couldn’t sit on, art deco lamps we couldn’t turn on, and glass-fronted cabinets filled with gold-rimmed china we couldn’t put food on. When I came home with a paperback, or a polyester sweater, or a bead trinket paid for with my babysitting money, my mother never asked, “Do you love it?” but only “How much did it cost?” A question of mine also went unasked: “How much was I worth?” What would my mother have said? When my grandfather deserted her, my mother lost love and money. The two became one and never enough.

One day, my mother purchased her own engagement ring, a white gold band twisted to resemble a rope studded with tiny diamond chips. After so much sorrow, perhaps their marriage had lost its luster. Perhaps so had my father’s engagement ring. Perhaps taking it off was the best my mother could do as long as she considered divorce anathema. Perhaps she envied her friends’ modern rings that sparkled so gaily. Perhaps she had other reasons. I only know that off my father’s engagement ring went from her hand and into a narrow safe deposit box, that long-ago appraisal secured around it with a rubber band. For as long as my mother was alive my father’s engagement ring stayed far from the light it could so easily catch and spin. Radiance. Darkness. My father’s engagement ring was complex enough to hold both.

I want to make this into a simple story: a placid, loving man makes a mistake and marries an angry, money-loving woman. But the truth is there was a time in my parents’ lives I never knew. When my father was robust. When my parents were glad to be alive. Glad to be in love. Glad to be together. A time when the door to the future was open; the vista was wide, luminous. A time when they hoped for my sister’s birth. When they hoped for mine. A time when my sister and I were loved and happy and safe in that love. But the radiant future my parents glimpsed became the darkness our family lived.

*

They say the ring finger connects to the heart but it also connects to the wallet. The year my mother died my daughter was in first grade. She couldn’t recognize the letters of the alphabet. She couldn’t connect the sound of a letter to its visual image. We found a one-on-one reading program, research-based and research-validated. First there was one summer of tutoring for five days a week, seven hours a day. Come the fall, there were Saturday mornings and one after-school session weekly. Then came another summer of intensive tutoring, just a few weeks this time, and another summer after that. We couldn’t afford all the tutoring; my daughter couldn’t afford to not know how to read. Out of vaults, out of a safe deposit box, out of darkness came my father’s engagement ring. Off to a West Seattle jewelry store for appraisal, purchase, or consignment it went along with my mother’s gold link bracelets, her gold rope chains, her diamond earrings, a sapphire pendant with matching earrings, broken Rolex silver watches from the 1960s, pearls and topaz and emeralds.

The jeweler had grey hair and wore a grey suit and owned a third generation family business. He knew the worth of another family’s cast-off jewels. His wrinkled hands sorted quickly through the hoard spread atop his glass case. Under that glass rows of ruby earrings, emerald bracelets, and gold and silver and platinum necklaces gleamed. He picked up my mother’s gold-link necklace with matching bracelet and earrings, then tossed them aside. Gold plated; not real gold. The sapphire pendant with its matching earrings? Glass. The diamond stud earrings? One pair was zircons. One pair was real diamonds but poor quality. My mother’s own “engagement ring” with its rope twists of diamond chips? Cheap. Cheap. My father’s engagement ring?

The jeweler’s eyes widened. He reached for my father’s engagement ring with all the dignity of a hungry child in a cupcake store. A ring like this, he said, could go for a lot if we sold it ourselves on Craigslist. Have a stranger come to our house? Promising to bring cash? Arriving instead with a gun? An accomplice? We’ve all heard those stories. What was more valuable, the money or our lives?

The ring languished on consignment. Sunlight poured on it through the windows, and my father’s engagement ring seemed to again dance in the light. Happy couples came inside the store; a few made offers. Two thousand. Wait, said the jeweler. Forty-five hundred. Wait, said the jeweler. The estate sale buyer’s offers were little better. Wait longer, said the jeweler.

I needed money. There was no saving my parents’ long gone marriage, but my father could still have his love, his hopes affirmed. A good price? I could hold out for that and finally, I got it. My father’s granddaughter now reads. She reads age-appropriate books. She reads chapter books. She reads slowly, but she finishes each book. She loves to read.

My father’s engagement ring wasn’t my only inheritance from my parents’ unhappy marriage. A ring is just metal worn around a finger. Diamond. Platinum. A ring is not love. What’s love but how you live your life in your minutes, hours, days? And what’s money but the minutes, hours, days of your life spent working for the means to nurture what you love? This is a story about money, after all, and now in my family, money does mean love.