An Interview with Sonja Livingston, Author of “Queen of the Fall”

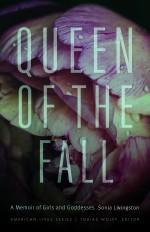

Sonja Livingston is an award-winning memoirist whose work has appeared in countless literary journals and several textbooks on writing. Her newest book, Queen of the Fall: A Memoir of Girls and Goddesses, is a collection of lush vignettes that explores, through her own experiences and the lives of others, what it means to be a woman in our world. She writes about sorrow and sacredness, and the beauty that is found in both. Her essays consider Greek mythology and Roman Catholicism as well as famous women like Susan B. Anthony and Ally McBeal, but always she comes back to the personal: her own femininity, fertility, and family . . . and her own heartache.

Queen of the Fall is not to be read hastily. It is a book to bring out in a quiet moment, and each short essay is a sweet fruit to be savored. Perhaps Livingston’s own words can describe the experience best: “What to do with such language? What to do but take it in a line at a time, stopping now and again for breath? What to do but swallow it whole, until saplings take root?”

In the following interview, Sonja talks about her new book and shares some writing wisdom.

Queen of the Fall is a collection of vignettes that creates a beautiful (often sorrowful) meditation on women and girls. How did this book come together?

I didn’t know I was working on a collection of essays. In fact, having published one memoir, I thought I was done with personal nonfiction. I wrote some poetry and short stories, but found myself returning again and again to the essay form, which—despite the lovely pull of poetry and the red hot sizzle of fiction— I’ve finally accepted as my literary soul mate. As I wrote, certain concerns, such as femininity and fertility naturally arose, and, as you say, often took on a sorrowful note. I don’t think of myself as an especially sad or even serious person, but many of the essays explore loss, and, in particular, how certain aching is related (even necessary) to the beauty of living.

In many of the pieces you explore quite personal topics—your struggles with fertility, the dissolution of your first marriage . . . What was it like to lay all of that bare? How have family and friends responded?

A little self-delusion can be a good thing, at least while you’re writing. If I let myself think about how exposed I might feel or who might be offended when the work is published, I’d never write a thing. And actually, Queen of the Fall was just selected for a citywide reading program in my hometown, so I can’t pretend that it won’t be read.

I do feel vulnerable in certain essays and fear risking offense in others, but despite those feelings, I want others to read and connect to my work. I was careful about what to include and took care to protect others, but some of the subjects are still tender. What guided my decision about what to include was whether the essay seemed to arrive somewhere beyond the personal or painful experience in which it began.

As for how others have responded, while no one has complained, it can’t be fun to be reduced to a character or symbol in someone else’s story (no matter how sympathetically or beautifully we render them). The fact is that our lives are interconnected and I struggle with what we memoirists often must do, which is to write our version of other people’s lives as part of telling our own stories.

In “Flight” you describe essay writing as “this form that made an art of an attempt—for what is life but a series of efforts?” What can you tell us about your writing process? What happens when you sit down to make “an attempt”?

I most often arrive at the page with a swirl of disparate images, words or questions and start writing in a way that feels like flinging a bunch of paint on a canvas simply to get the stuff down. Then I come back and do it some more, noticing which colors and patterns seem to stand out. At some point, the combination of writing and internal processing that goes on away from the page starts to come together, and a shape begins to suggest itself.

Because I believe that we humans are always trying to make meaning, I trust that what we notice matters somehow, like a bagful of arrows we carry around. My goal in writing is to explore those ideas, following where they lead.

The wonder of the essay is that it gives physical form to the mind at work, illuminating our thoughts, making connections, stumbling across ideas and meaning we couldn’t have expected before the writing began. Maybe all writing is this way, but the essay allows its writer to lay her questions bare, to speak them outright, or to follow whispers and hints until they become a unified and distinctive voice. The flexibility of the form fits my process, the way it allows for expansiveness and directness at the same time, so that I can begin a piece about a child who came to me for counseling with the question—What brought her to me the day the teacher played Mozart in music class?—not knowing the answer, but keeping at it to see what I might see. That’s the attempt—the gorgeous attempt—of the essay.

You also wrote an award-winning memoir, Ghostbread, about growing up in poverty in the 1970s. How was your experience writing Queen of the Fall similar or different to the creation of Ghostbread?

As a person, I’ve grown and changed, my interests and perspective and goals. All of this is reflected in the writing, especially in nonfiction where the voice of a piece is so obviously the writer’s. As a result, the biggest difference was that I found that my voice had changed. Or the voice I’d harnessed to write the material was different. Ghostbread was gritty and raw because it explored a time when life was gritty and raw. The essays in Queen of the Fall, by contrast, tend to be more meditative and lyrical. While both books are concerned with memory, my focus changed a bit, as well. While I remain concerned with poverty and social class, my interest in the lives of girls and women took a more primary role in Queen of the Fall.

In this issue of Compose we published a piece from Queen of the Fall: “Our Lady of the Carpeted Stairs.” It seems like Catholicism was a fascination of yours when you were younger and continues to be something of a muse for you in your writing. Do you agree? What can you tell us about your interest in Catholicism and its symbology?

I’ve always been a sucker for language and mystery. As a kid, the sources for those topics were as follows: 1.) Nancy Drew, 2.) Greek Mythology, and 3.) Corpus Christi Church.

In “Our Lady of the Carpeted Stairs,” the church is the setting and the priest and the Virgin Mary, the figures I use to explore the concept of adoration. If I’d grown up Baptist or Quaker, I would have made use of different symbols to explore that same concept. That said, Catholicism was and is important to me. Church was one the few relative constants in an unstable childhood. In many ways, it became home. It helped that our church was so progressive it would later split from the mainstream church (for ordaining women). It was a place of incense and candlelight, but also a place where parishioners sported Birkenstocks, boycotted grapes and Nestlé, and organized war protests. Church wouldn’t have been a sanctuary for me if it had been filled with fearful messages or I wasn’t allowed to be an altar server because I was a girl. I still occasionally attend Mass because there’s something I get only by sitting in those wooden pews, soaking in the stained glass, listening to the priest’s voice rise into song.

You have a gorgeous book trailer for Queen of the Fall on your website. Tell us how that came to be.

Thank you! Wow. I feel like a kid whose mother just put her over-glued construction paper art project on the fridge! I made it, Ma, I made it! The truth is that I’m not very technical and wasn’t sure about trailers, but many of the essays’ subjects, especially those featuring feminine icons, are quite visual and lent themselves to a video collage.

Queen of the Fall is part of the American Lives Series. What can you tell us about this series?

It’s a wonderful series that publishes literary nonfiction (memoir and essays) in a wide variety of topics and forms, all of which highlight and reveal different aspects of American lives. The series includes books by writers whose work I greatly admire and regularly teach. Writers like Peggy Shumaker, Dinty W. Moore, Lee Martin, Sonya Huber, Harrison Candelaria Fletcher, Sue William Silverman, Mary Clearman Blew, Joy Castro and many others. For nonfiction nerds like me, it’s kind of a literary Valhalla.

You teach workshop classes in creative nonfiction for the MFA program at the University of Memphis. What is one of the best pieces of advice you give to your students?

Students tend to be very serious about writing, and I get it. They’re accruing debt and working hard for a degree whose worth is debated (or debased) five times a day. They want to write something that matters and can be published and often want to decide right away precisely what that book or essay will be. The advice I most often give is this: Slow down. Play with form and voice. Trust.

No one wants to hear this. I don’t want to hear this. When we write, we want to know that all those hours hunched over the computer with our hearts torn open will pay off. The good news is that it always will, it always does. But the hard part, the terrible, glorious, pain-in-the-ass truth of it, is that we can’t know when we begin the wondrous shape, texture and tenor the writing will eventually take.

About Sonja Livingston

Sonja Livingston‘s latest book, Queen of the Fall, was published this spring as part of the American Lives Series at the University of Nebraska Press. Her first book, Ghostbread, won the AWP Prize for Nonfiction and is taught in classrooms around the country. A new essay collection, Ladies’ Night at the Dreamland (forthcoming, 2016) blends memoir and biography to provide poetic profiles of fascinating but often little-known historical women. Sonja’s writing appears in many fine journals and has garnered awards from Arts & Letters, the Iowa Review, New York State Foundation for the Arts, the Deming Fund for Women. She teaches in the Creative Writing Program at the University of Memphis. www.sonjalivingston.com