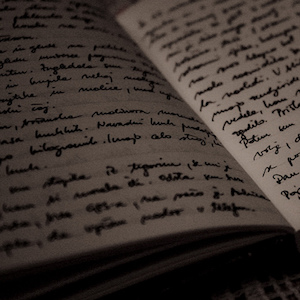

Writing in the Dark

Today’s post is written by special guest Todd Outcalt.

For the past forty years I have written, primarily, in the dark. This habit, however, was not one born of preference, but of necessity. During the day—when the sun is shining and all is right with the world—I have worked diligently in the lengthening shadows of the Lord’s vineyard, to earn a living, to support a family, to make my way. And I have worked, if I can admit it, most often seven days a week, with little or no break on the weekends. In fact, pastors have no weekends in the common experience, but most, like me, tally forth across those forty-eight hours of a Saturday and Sunday through sermon after sermon, through hospital visitations and speaking engagements, and the exhausted appearance that is born of observing other people’s recreations and relaxations from afar.

That is why I write in the dark.

For the past forty years I have risen, most mornings, long before the sun to get at the meat of writing. Writing and exploration that has taken me on wild flights through the universes of science fiction, or mystery, or even romance, or has landed me squarely in Galilee reflecting on some austere parable of Jesus, or poetry perhaps, or humor, or even writing essays for bridal, fitness, and outdoor magazines. I have written all of these and more—some thirty books, by now hundreds of articles, and so many poems I can no longer keep track of the hundreds of floppy disks that contain them.

I have written most of this material in the dark. Most of it in darkness so severe, so silent, so numbing that I often feel displaced when my wife walks down the steps at 5 a.m. and interrupts me with her morning coffee. By then, I may have written in the darkness for hours, and when I bring a writing session to a close, I know I am not finished for the day. The sun will rise. I will drive to the gym, or shower, then dress and drive to the office. Then I work. I have, I hope, later time for conversation over an evening meal, perhaps another meeting or two at the church, and then I am back home again. In darkness. And like Mike Finnigan—I begin again.

I write in the darkness. Sometimes until I fall asleep in the chair or draped across the couch. Sometimes I write until my wife yells down at me from the balcony at the top of the steps. She wants me. For something. Sometimes.

Or, I write in darkness until my fingers grow numb. Until I cannot feel the tips of them, or they have grown hard and calloused from punching at the sweating keys. I write in the darkness, sometimes keeping track of the word count—my daily output, my goal for the week, all the deadlines I must meet. Daily deadlines. Weekly ones. Others looming further out on the horizons of months and years. I type up another thousand words. Or two thousand. Or five. Doesn’t matter. I write in the darkness until I cannot write any more. Until my thoughts begin to slip away from me like butterflies out of a wide net. I cannot capture them any longer. There are too many of them and soon the sun will rise and I must work.

I write in the dark. As I wrote this essay in the dark.

But I have imagined: what would it be like to write in the daylight? What new stirrings, what fresh thoughts, what sights, what sounds would I encounter sitting beneath the shade of the sycamore surrounded by a full sun? Would my writing take on the overtones of spring? Would I see life differently, or even the words on the page, if my output was carried along by cirrus clouds instead of the dim light of a sickle moon? How much more love could I express, would I express, if I wrote under the pseudonyms of April showers or High Noons? What would it be like, I wonder, to create a full swath of words working in the solitude of day?

I have, of course, experienced some of this. But only in snatches.

Sometimes, writing on my day off, I have lingered on the back deck far past the peak of sunrise, clad only in underwear, staring up at the sun as it washes out the glow of my laptop computer screen. I have stood in the middle of afternoon showers, arms outstretched, dredging up memories and poetic incantations that I hold in my memory and on the tip of my tongue for later. I have hiked paths, written my name in the sand. I have passed this way.

But the daylight . . . the daylight is for living, for loving, for working. The light is distracting. I see things about the world, I acknowledge things about myself, that I would never admit in the darkness. The light is for seeing. For knowing.

It is easier to imagine in the dark.

But I want to write in the daylight. The darkness seems temporary to me—as if I am earning my way to another shift. I embrace the darkness each day because I yearn for the light. I have conversations with myself in the darkness, urging my courage, my fortitude, to hold out for another day, another week. Some day you will write in the daylight, I tell myself. There will be time to sleep then. Or death. Whichever comes first.

I write in the darkness as the moon rises against the trees or as it transoms across the transparent clouds. I write in the darkness so that those whom I love will not have to know what the darkness is. I write so they can sleep, so they can live in the light. Sometimes I write in the darkness in order to watch for the arrival of the light—a new day as it smiles and creases the corners of the horizon. The arrival of the light, the departure of it, seems the most stirring to me. The most fitting. The most inspiring. Light is what we yearn for.

But I dream of the light. Most of my dreams are of the light. Of the day. I want to see what I’m getting.

Sometimes I dream of writing on the beach, under a blazing sun. I have no idea where the electricity comes from. I am writing an article about sailing (and I don’t sail) or perhaps a love poem. And yes, there are times when I awake in the middle of the night—in deep darkness—and I take up pen and paper by the side of the bed and write down full-blown paragraphs dreamed complete, some of them coherent. Later I rise before the sun and turn these into thoughts, and the thoughts turn into pages. This is my dementia. These are the essays I write, the articles, the books.

I write in the darkness. I admit it. I write. Soon . . . even today, there will be another deadline to meet. Another editor will write.

Or my agent will call. She will phone me after she has been awake for hours and has gathered a full head of steam and she will ask me if I have been writing.

I will tell her the truth.

That I have been writing in the darkness, writing for hours, but dreaming of turning it into light.

About the Author

Todd Outcalt is the author of thirty books in six languages, including Common Ground (Skyhorse), Candles in the Dark (Wiley & Sons) and The Best Things in Life Are Free (HCI). His work has been included in such magazines as Leadership, American Fitness, Cure, and Newsweek.