“to see if great minds really do think alike”: A Conversation between Grace Bauer and Laura Madeline Wiseman

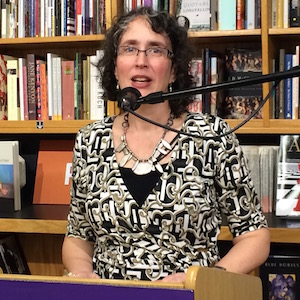

Today we welcome poets Laura Madeline Wiseman (we published three of her poems in our Fall 2013 issue) and Grace Bauer.

Grace Bauer’s newest book of poems is Nowhere All At Once, just out from Stephen F. Austin State University Press (February 2014). Her previous books include Retreats & Recognitions, Beholding Eye, and The Women at the Well, as well as four chapbooks (Café Culture, Field Guide to the Ineffable: Poems on Marcel Duchamp, Where You’ve Seen Her, and The House Where I’ve Never Lived). She is also co-editor, with Julie Kane, of the anthology Umpteen Ways of Looking at a Possum: Critical & Creative Responses to Everette Maddox. Her poems, essays, and stories have appeared in numerous anthologies and journals. She teaches in the creative writing program at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Laura Madeline Wiseman is the author of Queen of the Platform (Anaphora Literary Press, 2013), Sprung (San Francisco Bay Press, 2012), and the collaborative book Intimates and Fools (Les Femmes Folles Books, 2014) with artist Sally Deskins, as well as two letterpress books, and eight chapbooks, including Spindrift (Dancing Girl Press, 2014). She is the editor of Women Write Resistance: Poets Resist Gender Violence (Hyacinth Girl Press, 2013). Her book American Galactic is forthcoming from Martian Lit Books. Wiseman has a doctorate from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. She has received an Academy of American Poets Award, the Wurlitzer Foundation Fellowship, and her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Prairie Schooner, Mid-American Review, Margie, and Feminist Studies. Currently, she is a writer-in-residence at the Prairie Center of the Arts in Illinois. www.lauramadelinewiseman.com

A Conversation between Grace Bauer and Laura Madeline Wiseman

Laura Madeline Wiseman: Your new chapbook Café Culture reminds me a little of Ellaraine Lockie’s new chapbook Coffee House Confessions in theme. Both of you depict the coffeehouse and those peopled inside it. In her book No Logo Naomi Klein discusses the third space of coffeehouses—the space of not home and not work that people frequent to engage in a multitude of tasks—write, socialize, eat, caffeinate, linger. I’m always curious about where writers find inspiration and where writers write new work. Where do you write and, more specifically, where did you write the various poems you’ve collected in Café Culture?

Grace Bauer: I haven’t read the two books you mention, so I’ll have to look for them—to see if great minds really do think alike, at least about cafés. As for my chapbook, Café Culture originated with a kind of diversion. I normally write at home, where I have a “study” reserved for that purpose, but I do frequent various coffee shops—both national chain kinds of places and more local independents, though I prefer the latter. Over a period of time when I was writing some poems that were pretty emotionally heavy, or when I was feeling a bit of a writer’s block or just needed a change of scenery, I would head out for one or another of the coffee shops or breakfast places in Lincoln with the specific goal of eavesdropping and/or observing whatever there was to hear or see (in addition to getting my caffeine fix). I’d just sit and sip coffee until something caught my attention and then start taking notes. I did that off and on for a couple of years, and still do it from time to time. Most of what I come up with—then and now—is junk, but sometimes a piece would take on a life of its own and develop into a poem that felt like “a keeper,” even if it didn’t fit into the manuscript I was working on at the time.

Then I took a trip to France. I spent a few days on my own in Toulouse and Albi, and then went to a workshop with my friend Marilyn Kallet at the VCCA in Auvillar. In France, of course, the café is a way of life—and the ambience is different than the American coffee/house/shop. So that led to the poems I put at the end of the chapbook. There was no grand design in mind when I began; I was just “priming the pump” of writing, so to speak. Once I had a bunch of poems, I started arranging them and came up with what I thought made a cohesive and entertaining chapbook. I sent them to Dan Nowak at Imaginary Friend Press and he agreed. And voila!

I do think your observation about the café/coffee house being a kind of “third space” —both public and private—is true. Some people are there to purposely be alone in a crowd. To see and be seen. Some people seem to use the places as their private offices—though a few are strangely (and, I’d say, obnoxiously) unaware of how public they’re being with their private business. There’s something almost ritualistic in how people approach food and drink, so cafes are great places to people-watch—whether we’re talking the American, French, or any other version of them.

GB: Both Queen of the Platform (your new full-length collection) and First Wife (your newest chapbook) are series of poems exploring women’s stories. Queen of the Platform begins in the historical (your great-great-great-grandmother, Matilda Fletcher Wiseman) and First Wife in the mythic (our ur-mothers, Lilith and Eve). Talk about your interest in preserving and re-telling women’s stories and on the process of writing poems based on research and pre-existing texts.

LMW: I love the idea of going to coffee shops as a writing diversion, a diversion that turned into a chapbook. Before starting this interview with you, I’d read your previous collections, taught Beholding Eye, and spoke with you in The Chapbook Interview series. Previously, I asked you about your obsessions. In the closing essay in Women at the Well you wrote, “I often like the bad girls best” (84); “It’s those often nameless women that get me” (86). These women, you said “seemed to insist that I write about them” (86). That insistence from characters to be written about has been a crucial part of what propels me to write certain series. However, there’s another part of me—perhaps the researcher, the scholar, the post-PhD student, the learner—that wants to know more, that propelled me to write Queen of the Platform and First Wife.

LMW: To write Queen of the Platform, I began a journey in which I researched suffragist and lecturer Matilda Fletcher Wiseman, who was also my great-great-grandmother, a woman about which very little was written. The family members who introduced me to her said only that, “She spoke at Chautauquas while her stepchildren sang and danced.” They knew little about Matilda, but one of them allowed me to borrow the scrapbook Matilda kept for the first five years of her career. In this scrapbook she pasted announcements of her talks, her essays that were published in the Iowa State Register (later renamed The Des Moines Register in 1903) and excerpts from her poems and lectures that were reprinted in newspapers. The more I researched her, the more I wanted to know, primarily because I had never known that a woman in my family spoke to support herself and her family in a time when women were not the primary breadwinners. In 1869 at the age of twenty-six she started speaking, a career that spanned the next forty years of her life until she died in 1909. This research and writing shattered my assumptions about my female ancestors and the life pursuits of women in the Midwest in the late 1800s. It also gave me new insights into the lives of women like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, women whom Matilda joined on the stage. I had to tell Matilda’s story, because I had to know Matilda’s story myself. Similarly with First Wife, I wanted to understand the Lilith myth deeply and fully, and for me, to do so meant to write it.

GB: What you say about Matilda reminds me of Virginia Woolf’s proclaiming, in A Room of One’s Own, that “anonymous was a woman.” How many women—social/political leaders like Matilda; artists like Artemisia Gentileschi, who I write about in Beholding Eye; biblical “bad girls” like Lilith, who get written out of the story altogether; or the many others who are reduced to “wife of” in the official versions—are rendered anonymous and/or invisible? Revising that invisibility, naming the anonymous, is something I think we have in common in (at least some) of our work. Adrienne Rich has said that this kind of revision is, for women writers, “an act of survival.”

LMW: I’m interested in place, particularly how one marks place in a series. In Queen of the Platform, I sought to offer the flavor of the stage, the trains, and feminist gatherings. Café Culture offers the place of the third space. At times, Nowhere All at Once offers place in the form of home and neighborhood, reminding me of Naomi Shihab Nye’s Never in a Hurry, but also moves beyond that to places of travel. What’s your interest in place?

GB: As for an exploration of place in Nowhere All At Once, that’s an interesting observation. I see this book as a fairly eclectic collection, though there is, as you say, a good deal of focus on place and/or dis/placement, and, I think, perception. The title poem, for instance, begins with the speaker looking down on the Plains from a plane—seeing that flat expanse of land below like a huge abstract painting or patchwork quilt. “Sight/Seeing” explores how differently we look at places when we’re traveling—how the very expression suggests that seeing is the whole point of taking “a trip”—though clearly there are “sights” no matter where we are. Other poems explore how we look at people: “Crime Scene”—how we often try not to look at the homeless; “Our Waitress’s Marvelous Legs” —how we can’t help looking at people who are heavily tattooed and how, perhaps, making yourself “something to look at” is the whole point of getting those tattoos. I’m not sure I come up with any brilliant conclusions or answers in the poems. Maybe raising questions is more the poet’s job. What do you think?

LMW: I do think raising questions can be a poet’s job and for me, writing the poem is one way I answer questions for myself. Queen of the Platform answers the question: who was Matilda Fletcher? It’s not the answer, but it is an answer.

GB: Let me jump onto another train of thought. The majority of your poems are written in free verse, though you sometimes employ so-called “fixed” or traditional forms—the sonnet, the ghazal, the villanelle, the sestina, etc. Was/is this a conscious choice on your part? Or did the poems evolve into their more formal structures as an intuitive part of the process?

LMW: Some poems arrive in form, while others in Queen of the Platform I worked towards writing them. Form was the frame to hold the content. I am a student of traditional form and I appreciate the reexamination of form by contemporary poets. Maxine Kumin wrote, “The harder—that is, the more psychically difficult—the poem is to write, the more likely I am to choose a difficult pattern to pound it into.” The poems in section III were difficult to write—psychically yes, but also culturally—because the content didn’t fit within the narrative arc of the book’s persona poems. “Documentations: On Matilda’s Talks” is a three-part found poem, the first on Matilda’s lecture to free a woman murderer, the second on her talk to challenge an establishment falsely claiming to offer housing to women in New York City, and the third on her address at the Nebraska State Fair in 1873 to encourage equality in marriage. I wanted poems in Queen of the Platform to offer up a taste of the linguistic phrasings of nineteenth-century newspapers, especially how they recapitulated and paraphrased her two hour lectures. To savor that language, I employed the ghazal, the sestina, and the acrostic. In their chapter on meter, rhyme, and form in The Poet’s Companion, Kim Addonizio and Dorianne Laux write, “We don’t often enough read poems aloud, to let the language vibrate through our rib cage and vocal chords, to savor the delicious taste of syllables on our tongue” (139-140). Form gave me a way to hear and offer up the sound and music of Matilda’s day.

GB: First, let me respond to your answer—and mention the sad coincidence that I’m reading it, and your reference to Maxine Kumin, the very day I hear that she has died. It’s a loss to the poetry world. I think what Kumin says about using a complex form for a poem to help liberate difficult subject matter is true–or can be true. It can facilitate the process of silencing one’s inner censor. Molly Peacock has said something similar. As for your attempt to “give the reader a taste of the linguistic phrasings of nineteenth-century newspapers,” I think you achieve that brilliantly. It’s one of the things that draws us into the entire world of Matilda’s story. I love what you do with “Documentations” and with “Telegraphs To Geo,” where you produce not just the clipped language of the telegraphs, but the visual appearance as well.

LMW: I have a strong interest in humor and poetry. While reading Nowhere All At Once, I couldn’t help giggling at the “Great Plains Prayer,” the poems where the persona/poet is startled by creatures (because who hasn’t been?), and “The Persistent Popularity of Angels,” to name a few. Even the title of the latter makes me chuckle. Can you talk about the use of humor in poetry and how one conveys it in poems?

GB: Using humor in poems is not something I plan or think about on a theoretical level, it’s just part of my world view, how my eyes see or my brain works or whatever. I don’t know how not to see the world as a little absurd. The animal poems you mention and the beach poems might be an example. I can recall a specific day when I was walking down the beach alone and the sand was littered with hundreds, maybe thousands, of these perfectly round clear jelly fish. The first thing that popped into my mind was that they looked like silicone breast implants. The second thing that popped into my mind was “this is why you will never be Mary Oliver.” I love a lot of Mary Oliver’s poems, and I have felt that sense of mystical awe in nature that she writes about so often, but my own poems never quite come out that way. Instead of some cosmic epiphany, I’m seeing breast implants littering the beach! Even the “Corsons Inlet” poem, where I was intentionally channeling Ammons’ beautiful meditation, there’s that one moment when I see the woman with the cell phone at her ear—that actually happened—and “strange shell” was the first thing that popped into my head. So maybe it’s just that my muse sometimes moonlights as a stand-up comic.

I’ve heard actors lament the fact that playing a comic role never gets the same respect as a dramatic one–though they claim it’s at least as hard to pull off, maybe harder. I think the same is true in poetry to some extent. Poems can be humorous without being “light”—or light weight—and the world needs all kinds of poems—free verse and formal, comic and serious–to help illuminate the human condition.

LMW: I do think the world needs all kinds of poems. I could hardly imagine a world without poets like Denise Duhamel or Julie Kane.

GB: Duhamel is a good example of a poet who uses humor to feminist ends. Julie Kane as well. And she’s also a good example of someone who uses formal technique to underscore her often biting humor.

Can I switch gears again, and ask you now about current or future projects? What are you working on now?

LMW: My chapbook Spindrift has just been released by Dancing Girl Press. It’s about mermaids. It’s a little bit of a retelling—certainly Ariel makes an appearance, as does the mermaids of Peter Pan—but more of a pondering like the point you made earlier on the poet’s job of raising questions. Spindrift asks who mermaids are and how we understand them. My next full-length book, American Galactic, should be released soon from Martian Lit books. It’s about Martians. Martians walked into my poetry and demanded I write about them. Martians make me laugh. After my fellowship at the Wurlitzer Foundation last fall, I made a side-trip to the International UFO Museum and Research Center in Roswell, New Mexico. Oh yes I did. You are right—the world is just a little bit absurd. Mermaids and Martians seem to be what I’m working on now, or maybe they’re working on me.

What about you?

GB: Mermaids and Martians–that’s an interesting combo. I’ll look forward to seeing those books. As for me—I’m on leave this semester, though I’m working with so many graduate students it has yet to feel like much of a leave. I’m spending way too much time writing letters of recommendation and departmental reports, rather than my own poems. I’m also doing some readings, trying to get some publicity out there for Nowhere All At Once and Cafe Culture—but I do have piles of finished (or nearly finished) poems spread across the floor of my study at the moment, trying to see if and how they might coalesce into a manuscript. I’m also working on prose—a series of interlinked essays that I hope to eventually weave together into a memoir. I’ve also just started what looks like another series of poems that might add up to a chapbook–though it’s too soon to know. I’m a bit superstitious about talking about things too early in the process, so I’ll leave it at that. As you say above, it’s hard to know sometimes what we’re working on and what is working on us. I guess as along as something is working, we’re okay. So, here’s to the next thing.