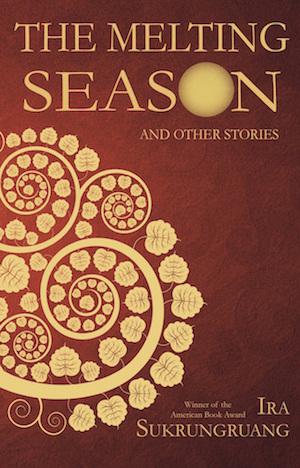

An Interview with Ira Sukrungruang, Author of “The Melting Season”

Ira Sukrungruang is a memoirist, poet, and the coeditor of two anthologies. He is the recipient of the 2015 American Book Award as well as several prestigious writing fellowships. His work has appeared in Post Road, The Sun, and Creative Nonfiction, among others. He is one of the founding editors of Sweet: A Literary Confection, and he teaches in the MFA program at University of South Florida. In addition, his short story collection, The Melting Season, was recently published by Burlesque Press.

The Melting Season‘s book jacket reads, “Mysterious, misfortunate, and often times strange, the characters in The Melting Season find themselves unexpectedly lost: in a blizzard, in a battle of rival restaurants, in the seat behind that cute girl in English class. What they discover—a disintegrating marriage, helpless fathers, the possibility of reincarnation—sometimes leads them to a greater understanding of themselves, and sometimes into darker shadows.”

In the interview below, Tawnysha Greene, another Burlesque Press author, asked Ira about his new collection.

The Melting Season is divided into five parts, each preceded by a quote from Julia Child. Can you give me some insight into why you organized the stories the way you did?

Julia Child is a sage. I, like many people, was obsessed about her life, her dedication to cooking and eating and drinking. I am obsessed with cooking and eating and drinking. It’s my life’s motto. What I was learning when I watched Julia, when I read her, was that she wasn’t so much instructing me on how to make a certain dish, she was teaching me how the process of learning to cook was the same process as learning to live. She was like the Buddha of the culinary world, and I was a novice eating up her every word. Pun intended. Because of this, I wanted to frame the progression of this book via Julia Child’s wisdom. The collection moves from the surreal to more concrete stances on life—even if these stances are delusions. Most of the characters in The Melting Season are stuck. They don’t know what to want. They have lived their lives with a sense of loss, but are unable to articulate what that loss is.

Why did you choose “The Melting Season” to be the title story?

The truth: The Melting Season was not the original title of the book. The truth: There were five other titles before this one.

The title story was something I kept secret, was a story I never sent out, a story written in a dark period of my life, a time I was battling depression. When I enter these darker periods, I tend to write fiction, because I don’t have to worry about the writer-at-the-desk and how smart he sounds. I can angst-out via my characters. I can get my darknesses out via the story. When I lived in the snow belt of New York, during the winters, the world was white. Surreal white. I wrote the story during one of those dark winters. And when spring came—and it always came late—the snow began to melt and suddenly what was lost is found. Layer by layer. Though nothing about the story is autobiographical, it is the most personal story I’ve ever written. Because of that, I kept it hidden. I protected it. Not until seven years later, when I met my editors—Daniel and Jeni, whom I trusted—did I bring the story out again. When I gave it to Daniel, he said that’s the title of the collection. Right there. He was right.

Who are your influences—professors or otherwise?

When I was an undergraduate at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, I studied with the late Kent Haruf, a teacher who showed me how to be as a writer. A teacher who lent me books by Raymond Carver and James Agee and Susan Minot and Sandra Cisneros, writers I loved and admired and wanted to become.

Kent made my fiction sharper, made me interrogate my characters, made me mine the worlds I knew, made me see the short story form as a way to explore the depths and vulnerabilities of people, and not something predicated on plot alone. Kent was also the one who urged me into the world of creative nonfiction. And for years afterwards, this was what I dedicated myself to. I stopped writing fiction, because I learned that before I can write and create the worlds of my characters, I need to know and understand and dig at my own world. I’m a writer who operates by constant questioning. Kent always asked questions. We would sit in his office, and he would be endless with questions—about the story, about my life, about life in general. He wanted me to arrive at a story through questions. Questions—the right questions—opens up a piece of writing, unites us, connects us.

Previous to The Melting Season, you published memoirs and a poetry collection. What was the writing process like in creating your first book of short stories?

My process of writing fiction contains elements of CNF and poetry. The language of it exists in the same language-creating brain space; however, for me, fiction occupies a different part of my mind, and the only way to explain it through metaphor. I feel when I’m writing fiction as if I am adrift on some floating island, and around me are other parts of this island, and I’m trying my damnedest to put everything together in a cohesive manner, and sometimes a part starts drifting away, and I’m madly trying to get it back, but by doing that, everything else starts to drift away, and suddenly I think, “Well, maybe it’s floating away for a reason.” I don’t know if that makes any sense. To me, some of the best short stories I’ve read are the ones that contain an element of absence, and in that absence we ask the readers in, we ask the reader to be part of our world.

Kent Haruf has been on my mind lately. It’s probably why I mentioned him. Every time I think of where I am now, I think of him. I miss him. I miss his words, his knowledge, his dedication to the written word. I read his novel Plainsong and think there is nothing more perfect than this book. He was not only a writer but the embodiment of all that is good about being human.

Many of the characters in this collection work in restaurants and eateries, so food and the love that goes into making these dishes are deliciously prevalent. Was this a conscious decision on your part?

We live in a culture of Food, with a capital F. We love it. We need it. I love it. I need it. Food brings hunger. Food brings appetite. Food brings desire. Food brings want. All of which are the foundations of what makes us human. All of which is essential to good writing. Holidays are about food. Family is about food. For me, the son of two Thai immigrants, food was the center of our lives. Food in Thailand is one of the most important parts of culture. Food is a serious business there. It’s everywhere, and it is delicious. A common Thai greeting is, “Have you eaten yet?”

Thai food in America is different. Some of it is good, but it’s not Thai. It’s a version of Thai. My life has been about this conflict. How do we remain faithful to Thai cuisine when there is no way to get all the right ingredients, especially in a temperate city like Chicago? Where do we find unripe green papaya? Where can we get pork neck? Where can we find fresh kaffir lime leaves? So we create something different. This difference is a mix of who we are and what we want. The food the characters make in The Melting Season is reflection of them. Something more complicated to this is the idea of authenticity of food. We create Thai food that is not Thai food, but rather Family Food. This collection is about that, too. Family Food. Family survival. Family.

One of the things I admired most about the stories in The Melting Season is the characterization and how skillfully you created each narrator. Can you give me some insight into how you write your characters?

The creation of character, for me, starts with voice. I have to hear them. I have to know the unusual ticks they have with language. I have to learn what shapes their voice—family, environment, pop culture, school, age. Where does their sarcasm come from? What makes them end sentences with question marks? I sometimes have imagined conversations with my characters. I ask them what their favorite food is. I ask them where they would like to live in twenty years. And then I delve into their bodily quirks. How do they react when they get nervous? What happens, physically, when anger takes its toll? Every emotion we feel starts first in the body.

What advice do you give your students at the University of South Florida, and how can we create characters as real and as vulnerable as the ones in The Melting Season?

I ask them to identify all the languages they speak. “Spanish,” they would say. “I took four years of French.” I then tell the class that each of them speaks at least five languages. Here are the languages I speak,” I’d say. French, though all I remember is mange moi, eat me. Thai, of course. But I also know Thai-lish, the language I speak with my mother, Thai-ifying English words, switching inflections and intonations, like strawberry into STLAW-bur-LEE or casino into CAH-si-NO. I speak the masculine language of the working-class South Side Chicagoan—guttural, words clipped, fuck used as a period. Fuck. I speak a different language with my lover, which is wordless, which involves the subtleties of the body. I speak a more formal language with my colleagues in the English Department—a political language, a cautious language. I possess the insecure “fat” voice, a voice that wants to hide, a voice filled with questions, like no matter how big I am, you still love me, right?

There’s more, I tell my students. They see what I’m talking about. They start sharing their other languages. The assignment, I tell them, is to write about one particular incident in their lives in five different languages. Give each voice no more than 200 words. When they return, they are eager to share. When they return, they say something that makes the teacher in me want to weep right then and there: “I really had to think about what I was doing,” they say. “I’m beginning to see what you’re talking about when you go on about language.”

Within each voice is a world. I want them to recognize that. I want them to see the infinite possibilities of character.

Your collection is published by Burlesque Press, the same lovely press that published my first novel. What was the publishing process like for The Melting Season?

I love Burlesque Press. I love their commitment to the literary world, their drive to be part of this beautiful thing called Independent Publishing. It is here we are seeing literature that take risks. We see literature that exists in the margins of mainstream culture. We see diverse voices, with diverse storytelling backgrounds. It’s where some of the best books I’ve read come from. I wanted to send The Melting Season to people I trusted, people who would be actively engaged in the production of the book. People who are dedicated not only in the product, but in the longevity of the product. People who are actively looking for different voices. People who see literature as tools to larger artistic engagement in a culture that seems to devalue the necessity of art. When I met Burlesque Press, when I saw the work they put into each book, when I see and hear about the extensive interaction they have with their authors, I knew I wanted to be part of this family.

What’s next for you after The Melting Season?

Too many things! I have a baby on the way, and I’m wondering whether I can complete everything. I have about five months to go, and the baby has taken over my brain. In fact, in my brain, there is a short story collection forming about this baby’s future, and all the mistakes his father will make along the way. And there will be joys, too. It’s an endless collection of fear and elation.

I’m at the point in my career where the joy is the writing, not the publishing. I keep thanking Buddha for this life. This life of the mind. This life of teaching. This life of being connected to this world. So here are the projects on deck: Three memoirs, The Year Between: Life After Marriage; Monk for a Month; Buddha’s Dog: Essays. I’m also working on a novel about ghost hunting—I’m obsessed about the supernatural—tentatively called The Cemetery. And a poetry collection, The Green We Speak. Of course I want to finish all these projects, and some of them are very close to being done. But if I don’t, I’m OK with that too. The thing about being a writer is that we write about life; we record what we see. I think I want to not record, not live through the notebook or computer screen, but through actually living and experiencing. At the end of all my classes, after we’ve slogged away for fifteen weeks, I always tell them, “Your last assignment: Go live life. Go live.”

About Ira Sukrungruang

Ira Sukrungruang is the author of the short story collection The Melting Season, the memoirs, Southside Buddhist and Talk Thai: The Adventures of Buddhist Boy, and the poetry collection In Thailand It Is Night. He is the coeditor of What Are You Looking At? The First Fat Fiction Anthology and Scoot Over, Skinny: The Fat Nonfiction Anthology. He is the recipient of the 2015 American Book Award, New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship in Nonfiction Literature, an Arts and Letters Fellowship, and the Emerging Writer Fellowship. His work has appeared in Post Road, The Sun, and Creative Nonfiction, among others. He is one of the founding editors of Sweet: A Literary Confection and teaches in the MFA program at University of South Florida. For more information about him, please visit: www.buddhistboy.com.