The Story Behind “In Retail” by Nana Adjei-Brenyah

Today’s post is written by Nana K. Adjei-Brenyah, whose story “In Retail” we published in our Fall 2014 issue.

“Hi, how are you? What are we looking for today?” The customer grunts, vaguely angrier than they were the moment before. They are telling you to leave but not bothering to spend language on you. This is common. In a single shift, you might say some variation of “Welcome, please buy stuff!” hundreds of times. Sometimes you’ll be completely ignored—as if your nametag granted invisibility. Sometimes you’ll be brushed off, like a gnat. Still other times, you’ll be engaged and made leader of a small party of hopeful shoppers. Maybe you’ll guide a single old woman who only speaks Spanish.

For me, the key to being a good salesman was sincerity. Or, at least, the projection of sincerity. Projecting sincerity hundreds of times over an open-to-close is a special kind of torture because it forces you to pretend to be the exact opposite of what you feel four hours into any shift: apathetic, and on bad days, homicidal. It takes some method acting. You need something good on your mind so that your eyes will carry your smile when you walk up to the ninety-sixth person and say, “Hey, how are you doing today? I think that jacket would look great on you.” You need to try to be happy even though, if you’re like me, almost everything about working retail feels a little bit like depression.

After far too many hours sacrificed to megalith malls in New York, “In Retail” is a slice of the grim reality of working a job that is inherently monotonous. Having only just recently left the retail world (hopefully for good), there was a surplus of experiences to pull from. When I sat down to write, it was the times when I could honestly be happy helping people in the store that demanded themselves to the page. The word “help” kind of guided the process. Times like when you can tell the customer is pressed for cash and the state of their child’s clothes has made the approaching school year feel like an oncoming train, or times where a customer needs a particular kind of sweatpants—grey, no logos of any kind—that abide by New York State correctional facility guidelines. These instances, instances where a salesperson might legitimately feel as if they were helping someone, seemed to be where I could get the most thrust for a story set entirely in a store in a mall. I settled on an older woman that didn’t speak English as the catalyst for the story because my dealings with people who did not speak English were consistently pleasant.

I tried to let the story come out how it wanted to come out. I thought, okay, so there’s this Lucy, now what? We need a customer—a Spanish woman. The language barrier was a nice little toy for me to play with, and from it came a pretty long digression about a Spanish teacher that still fit in the story. I hope. The completion of the sale helped the story tie itself up.

The Prominent mall is kind of an amalgamation of the Palisades Mall in Rockland County, New York and the Crossgates Mall in Albany. Both of which I worked, transferring between different branches of a store called “Against All Odds”. Since it opened, three or four people fell to their deaths in the Palisades mall. One woman fell on Christmas Eve, and I was thinking of her when I created Lucy.

I sometimes used the second person to allow the narrator to address the audience directly. Often, working in the mall, I was forced to train new employees. The story, in some ways, is the narrator’s training of the reader. But rather than spending time telling us how to tri-fold jeans or how to handle markdowns, his instruction is geared towards the skill most essential to success on the job: finding things that make jumping down to a violent death seem like a bad idea.

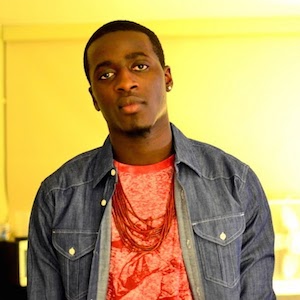

About the Author

Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah is currently working towards his MFA at Syracuse University. It is cold there, but he loves it. His work has been previously featured in Broken Pencil Magazine and Gravel Online Journal. He is from Spring Valley, New York, proudly.